Research

UNESCO World Heritage Site of Bridgetown and Its Garrison, Barbados, W.I.

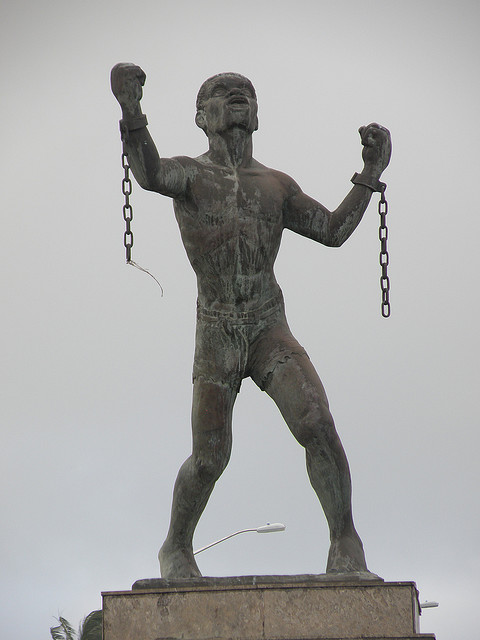

The focus of this project is the preservation of historic buildings and monuments in the island nation of Barbados and its connection with attempts to develop a heritage tourism industry. Although there is support for heritage tourism at the governmental level and in the private sector, there is still a great deal of ambivalence about how such an industry might take shape. Heritage tourism develops around the presentation of history to foreign and local visitors and therefore is tasked with the construction and dissemination of specific historical narratives. It is these narratives that are highly contested and it is here where the “politics of culture” is most clearly manifested. The fundamental question is: How does a post-colonial, post-slavery society preserve the monuments and buildings of its colonial past while simultaneously presenting a history that the local population can embrace? The question rests upon three underlying problems. The first is the role of tourism in the Barbadian economy and the need to create an additional source of revenue within that industry. The second is the role that history and historians have played in the development of the modern Barbadian national identity; specifically in relation to the treatment of slavery. The third problem has to do with the general public’s perception of what historic preservation is and who it serves in the larger community.

The focus of this project is the preservation of historic buildings and monuments in the island nation of Barbados and its connection with attempts to develop a heritage tourism industry. Although there is support for heritage tourism at the governmental level and in the private sector, there is still a great deal of ambivalence about how such an industry might take shape. Heritage tourism develops around the presentation of history to foreign and local visitors and therefore is tasked with the construction and dissemination of specific historical narratives. It is these narratives that are highly contested and it is here where the “politics of culture” is most clearly manifested. The fundamental question is: How does a post-colonial, post-slavery society preserve the monuments and buildings of its colonial past while simultaneously presenting a history that the local population can embrace? The question rests upon three underlying problems. The first is the role of tourism in the Barbadian economy and the need to create an additional source of revenue within that industry. The second is the role that history and historians have played in the development of the modern Barbadian national identity; specifically in relation to the treatment of slavery. The third problem has to do with the general public’s perception of what historic preservation is and who it serves in the larger community.

Beginning with the first problem it is important to understand the larger political economic role that tourism has played in Barbados. By the middle of the 1960s tourism began to surpass the sugar industry as the chief source of foreign revenue. As a percentage of GDP today the services industries account for nearly 80%. Traditionally tourism in Barbados has centered around the natural environment but it has also involved very high-end leisure activities such as yachting, automobile rallying and polo. Competition within the Caribbean region has led many islands to pursue tourism diversification which has included developing eco-tourism, adventure tourism, cultural tourism and heritage tourism. Barbados has sought the development of heritage tourism because it has a rich legacy of colonial buildings in the city of Bridgetown and an impressive number of historic plantation homes still intact in the countryside. The Barbados National Trust, founded in 1961 has, on several occasions, spearheaded initiatives to list, protect and preserve buildings seen as historically or architecturally important. These campaigns have met with limited success and sometimes outright resistance as the endeavor has, on occasion, been seen as elitist. Although there are generally rules in place to protect listed buildings, enforcement has been uneven.

The second problem that arises is related to the very desire to protect or preserve colonial buildings. The independence movement in Barbados was not only a strong nationalist movement it was also built on strong anti-colonial sentiments. In creating a national identity distinct from the former colonial power (England) the historians and intellectuals of the movement not only emphasized the African descent and culture of the majority of Barbadians, they emphasized an active and on-going resistance to slavery as a chief attribute of social relations during the colonial period. Thus, much of the history written about Barbados that arose in the 1960s and 1970s treats slavery as a combination of oppression and resistance and largely in rural areas. This history is significant and important but it does not tend to focus on the contributions that slaves made to the construction and development of urban centers such as Bridgetown. Thus, contemporary Barbadians see their role in the construction of historical buildings as minimal. Further, these buildings are often seen as the painful site of colonial oppression and domination as opposed to locations in which the enslaved survived and persevered. More recently studies that attempt to redress this balance have been produced, however it remains to be seen whether or not new kinds of historical narratives can shape popular or public opinion on colonial buildings.

The second problem that arises is related to the very desire to protect or preserve colonial buildings. The independence movement in Barbados was not only a strong nationalist movement it was also built on strong anti-colonial sentiments. In creating a national identity distinct from the former colonial power (England) the historians and intellectuals of the movement not only emphasized the African descent and culture of the majority of Barbadians, they emphasized an active and on-going resistance to slavery as a chief attribute of social relations during the colonial period. Thus, much of the history written about Barbados that arose in the 1960s and 1970s treats slavery as a combination of oppression and resistance and largely in rural areas. This history is significant and important but it does not tend to focus on the contributions that slaves made to the construction and development of urban centers such as Bridgetown. Thus, contemporary Barbadians see their role in the construction of historical buildings as minimal. Further, these buildings are often seen as the painful site of colonial oppression and domination as opposed to locations in which the enslaved survived and persevered. More recently studies that attempt to redress this balance have been produced, however it remains to be seen whether or not new kinds of historical narratives can shape popular or public opinion on colonial buildings.

The third issue at play is the popular perception of historic preservation and preservationists in the society. Seen primarily as the pastime of the leisured classes, who tend to be white, historic preservation and its advocates such as the Barbados Museum and Historical Society and the Barbados National Trust are often thought to be simply in the business of glorifying the dead age of colonial power. The most visible efforts at preservation are such things as sugar mills, plantation houses, colonial government buildings and military forts and structures. Although there have always been efforts to preserve and restore slave houses and although there are on-going archaeological efforts in former slave villages, these projects are not often well-known. Recently the problem of the perception of elitism in historic preservation has been exacerbated because current initiatives and programs to restore historic areas are presented as good for tourism, and by this it is usually meant foreign tourism. The general absence of local interest in preservation is not itself being addressed via, for example, local school-based educational programs, tours, lectures and classes available for the public. This constitutes an overall disconnect between local involvement with heritage and the governmental/private sector initiatives to enact preservation. Popular perceptions are, consequently, seen to be ignored or downplayed in the interests of accommodating a foreign market.

There are then three significant hindrances to the development not only of a “culture” of preservation in Barbados, but to a Heritage tourism industry that might take advantage of such preservation. My project addresses two points within anthropology and Caribbean studies. The first is the issue of the preservation of cultural heritage. The second is the issue of development and tourism within the Caribbean region. With regard to anthropology the issue of cultural heritage has emerged in recent years as a significant object of study. Generally the literature has approached the preservation of heritage from an archaeological standpoint, however increasingly the impact that heritage preservation has on the local political economy and culture of a given region has attracted scholarly attention. Yet, except for a very few important studies, these effects have not been systematically investigated in the Caribbean. Examining heritage preservation in the Caribbean becomes of crucial importance given the changing political and economic climate of the region in which the culture industry has grown dramatically as a portion of the gross national product of a number of countries, Barbados among them, and become an economic strategy by local governments in conjunction with other tourism projects.

White People: Images of Europeans by Non-Western Artists During the Age of Exploration, 1400-1830.

I am also, in conjunction with art historian James Harper, working on the development of a museum exhibition entitled White People: Images of Europeans by Non-Western Artists During the Age of Exploration, 1400-1830. This unique exhibition will feature representations of European soldiers, sailors, merchants, missionaries, explorers, and early colonists from the onset of European expansion to the beginning of the colonial period. The images offer insight into the host cultures’ response to the bodies, ideals and material culture of the “foreign” Europeans. Objects for the exhibition will be drawn from artists and cultural traditions that are global in scope including societies in Africa, Asia, the South Pacific, and Native North and South America. To this date, no such exhibition of this nature has ever been mounted.

The Concept:

This project inverts scholarly paradigms, and looks at the European encounter with its “others” from a fresh perspective. There has been ample scholarly attention paid to the modes in which the European and American observer has depicted non-Western peoples. Works such as Edward Said’s Orientalism (1978) or Stephanie Leitch’s Mapping Ethnography in Early Modern Germany: New Worlds in Print Culture (2010) consider the literary and visual image of Europe’s others, from early impressions to fanciful imaginings to the cataloging of populations according to the principles of what we now commonly refer to as “scientific racism.” Likewise, the representation of the Indian, African, Ottoman, South Asian and “native” Other has been well documented in a variety of museum exhibitions and attendant publications, such as the Walters Museum’s recent Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe (2012-13).

The reverse, however, has not been the case. Though the images made of Europeans by non-European artists have met consideration in isolated studies, they have not been treated comprehensively or comparatively. This is what we propose to do in the present project. A wealth of objects available for and relevant to such an exhibition exists, and it is our aim to gather together the most evocative and exemplary of these objects for the exhibition. Our aim in showing how non-Western peoples saw “whites” is “to dislodge them/us from the position of power… by undercutting the authority with which they/we speak and act in and on the world (Richard Dyer).” Our hope is to position Europeans and Europe not as the inevitable conquerors we take them for today, but as one of many societies who traveled, explored and interacted with the empires and villages of the non-Western world for over four centuries. Furthermore, by situating these images in their non-Western contexts and within non-Western traditions of art, we can begin to understand how Europeans were viewed and thought of. Were they seen as gods or demons or both? As potential political and military allies? As bizarre oddities from a distant world? Or all of the above? The different modes by which artists identify figures as European (modes that include physiognomy, cultural practice, costume and attributes) will shed light on the representational priorities of the host culture as well as on the nature of its encounter with the Europeans. The observations that the exhibition will enable should serve to remind us that Europeans, Africans, Asians etc. interacted hundreds of years before the concept of “whiteness” even existed.